Between December 1769 and March 1773, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his father Leopold undertook three journeys to Italy. During the first, lasting fifteen months, they visited many cities.

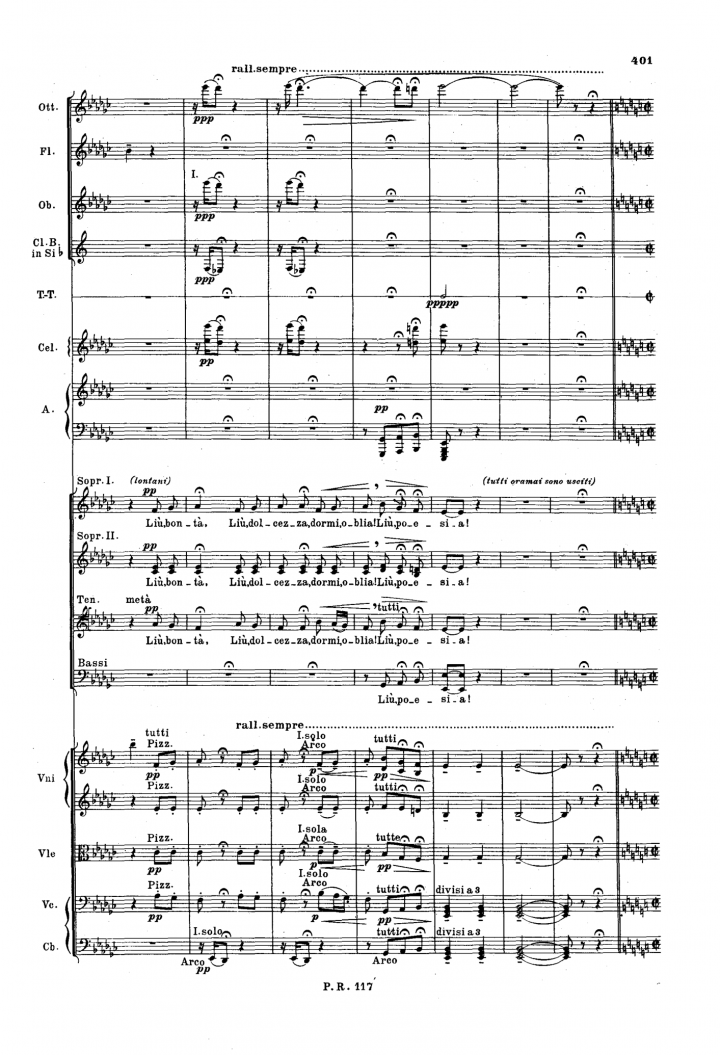

Fourteen-year-old Mozart in Verona in 1770. Portrait of Saverio Dalla Rosa (1745-1821). Source: Wikipedia.

In those occasions, Leopold Mozart organized some concerts, with the goal of showing his son’s virtuosity, ability as a composer and improviser, in front of nobles and sovereigns. Wolfgang received enthusiastic approvals, for example from Count Arco of Mantua, Governor Firmian, Archduke Ferdinand, Count Pallavicini, Pope Clement XIV, the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna and Accademia Filarmonica di Mantova, the Grand Duke of Tuscany.

Mozart and his father arrived in Florence on Friday, March 30, 1770, coming from Bologna, where Wolfgang was examined by Father Martini. Indeed, in October 1770, Wolfgang underwent an examination for admission to the Accademia Filarmonica di Bologna, presenting a four-voice antiphon composed in half an hour. After obtaining his diploma, Wolfgang received the title of “maestro di capela” from the Verona Academy.

Heading to Rome, they crossed the Apennines and entered Florence through the ancient Porta di San Gallo, staying at the Osteria dell’Aquila Nera on Via dei Cerretani. A plaque was placed at the corner of Via Cerretani and Piazza dell’Olio in 2006, to remember the 250th anniversary of his birth. The Mozarts were also received at Palazzo Pitti, attended the Morning Mass, and were invited to a musical academy (i.e., a musical gathering held at court residences, common at that time) at the Poggio Imperiale residence the following day. The academies were organized to demonstrate musical skills (e.g., with the harpsichord and the violin), and consisted in examinations of performing abilities, sight-reading challenges, and improvisations of arias or instrumental variations.

We know from Leopold’s letters that Wolfgang demonstrated his talent in playing and improvising.

With the exception of leopold’s letters, testimonies of Mozart’s brief passage through Tuscany are limited, and described Wolfgang’s performance without emphasis. The “Gazzetta Toscana” of April 7, 1770, highlighted Mozart’s talent and successes.

On that occasion Leopold wrote to his wife: “…I would hope that you could see with your own eyes Florence, the whole territory and location of the city. You would say that one should live and die here”.

Bibliography:

[1] Stefania Gitto, 2 aprile 1770: si esibisce a Firenze Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, in

“Portale Storia di Firenze”, Aprile 2014, http://www.storiadifirenze.org/?post_type=post&p=3759

[2] M. Solomon, Mozart, Milano, Mondadori, 2006.

[3] L. Bianchini, A. Trombetta, Mozart in Italia, Youcanprint, 2021.

[4] L. Chimirri, P. Gibbin, M. Migliorini (a cura di), Mozart a Firenze… qui si dovrebbe vivere e morire. Catalogo della mostra (Firenze, 22 settembre-21 ottobre 2006), Firenze, Vallecchi, 2006.