It all started in February 1924 with a sore throat that at first you had probably not given importance to. But, despite the remedies proposed by the doctors, that sordid disease did not heal.

Then they told you that you were serious, but you could do it. From your home in Viareggio you departed for Brussels with death in your heart, with the hope of being able to cure that terrible disease. You alternated between moments of despair and moments of hope.

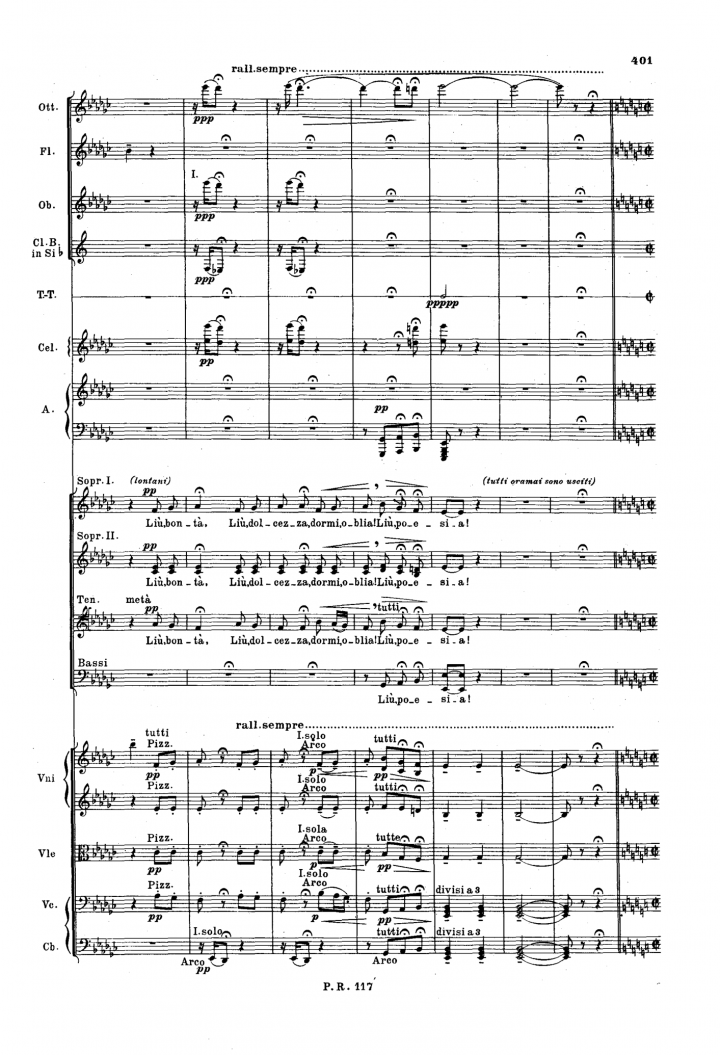

Turandot was there, unfinished. After composing Liù’s death procession, you interrupted the score with a E-flat minor chord, played by piccolo, violins, violas, cellos and double basses. But you wanted to, you had to heal, to finish your work. It only took a few days. You carried with you 23 sheets of sketches. You were thinking about the final duet. You wrote: “It must be a grand duet. The two almost otherworldly beings enter among humans through love and this love must at the end invade everyone on stage in an orchestral peroration” [1]. But you couldn’t work.

After Dr. Ledoux’s terrible surgery on your throat, which lasted 3 hours and 40 minutes, you couldn’t talk anymore. Your son Antonio (Tonio) put a block and a pencil in your hands and you wrote: “Will I be saved?”. Then everyone said yes, because the worst was over [2].

But it wasn’t true.

A few days later, on November 28 at about 4 pm, your stepdaughter Fosca was in your room, happily writing a letter to your friend Sybil Seligman to express her joy and hope about your recovery. But that letter was never finished. When Fosca went out of the room to find Sybil’s address, at about 6 pm, you suffered a heart attack and collapsed in your armchair [5]. Dr. Ledoux promptly removed the radium needles from your throat and make an injection [4]. But it was all useless. You spent a restless night, suffering from the torture of thirst, with a gasping respiration and an incessant tossing. You wrote on a paper: “I feel worse than yesterday – hell in my throat – fresh water”. You lost your patience when your son Tonio refused to go to bed. Your hands were constantly moving. At dawn of 29th, the Papal Nuncio Monsignor Micara arrived at the clinic with the Italian Ambassador Orsini-Baroni, called by Tonio. Tonio asked you: “There is Monsignor with Orsini-Baroni. Shall I let them in?”. You said yes, but only Micara was admitted at your bedside, on the pretext of visiting you, and gave you the last benediction. Then entered the nun who assisted you, and that you gently stroked and called Suor Angelica. She placed a bunch of violets in the room every morning, left by an unknown admirer for you in the porter’s lodge. She said that they were the violets sent by Mimì. She approached a small crucifix to your lips. Your agony began. In one last, tragic gesture of farewell to your loved ones, you raised your hand, as if to say goodbye to Fosca and Tonio, who were there next to you. Your fingers ran over the coverlet, as though they were playing some melody, your lips seemed to be whispering an accompaniment. After you had drawn two deep breaths, your head fell on its side [2][3].

On Saturday November 29, 1924, at about 4 am Giacomo Puccini, the most important Italian composer of the 20th century, died in Brussels.

That was the end of Italian melodrama.

References

[1] G. Puccini, letter to Adami, November 16, 1924

[2] G. Adami, Giacomo Puccini, Il romanzo della vita, Il saggiatore 2014.

[3] R. Specht, Giacomo Puccini, the man, his life, his work, 1933.

[4] M. Carner, Puccini, a critical biography, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1959.

[5] V. Seligman, Puccini among friends, The MacMillan Company, 1938.